This is an excerpt from a recent article at The Conversation. The writer is Phillip I. Lieberman, Associate Professor at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee. He has received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities. He is a social historian of the medieval Islamic world.

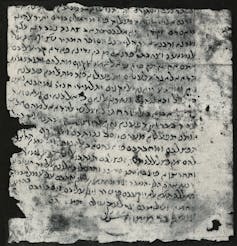

Plagues were a fact of life in ancient and medieval worlds. Personal letters from the Cairo Geniza – a treasure trove of documents from the Jews of medieval Egypt – attest that bouts of widespread disease were so common that writers had different words for them. They varied from a simple outbreak – wabāʾ, or “infectious disease” in Arabic – to an epidemic – dever gadol, Hebrew for “massive pestilence,” which hearkens back to language from the 10 plagues of the Bible.

Divine punishment?

Religious people throughout history often saw plagues as the manifestation of divine will, as a punishment for sin and a warning against moral laxity. The same chorus is heard by a minority today. As a Jewish person, I am embarrassed to read that a rabbi was recently quoted as saying that COVID-19 was divine punishment for gay pride parades.

In “A Mediterranean Society,” Geniza researcher S.D. Goitein describes Maimonides’ reaction to the plague: “Whatever the philosophers and theologians of that time might have said about man’s ability to influence God’s decisions by his deeds, the heart believed that they could be efficacious, that intense and sincere prayer, almsgiving, and fasts could keep catastrophe away.”

But the Jewish community also dealt with disease in other ways, and its holistic response to epidemics reveals a partnership – not a conflict – between science and religion.

Science and religion

In the medieval period, thinkers like Maimonides combined the study of science and religion. As Maimonides explains in his philosophical masterwork “The Guide to the Perplexed,” he believed that studying physics was a necessary precursor to metaphysics. Rather than seeing religion and science as inimical to one another, he saw them as mutually supportive.

Indeed, scholars of religious texts complemented their studies with science-centered writings. Maimonides’ Islamic contemporary, Ibn Rushd (1126-1198), is a perfect example. Though an important philosopher and religious thinker, Ibn Rushd also made meaningful contributions to medicine, including suggesting the existence of what would later come to be called Parkinson’s disease.

But it was not only elite scholars who saw religion and science as complementary. In “A Mediterranean Society,” Goitein says that “even the simplest Geniza person was a member of that hellenized Middle Eastern-Mediterranean society which believed in the power of science.” He adds: “Illness was conceived as a natural phenomenon and, therefore, had to be treated with the means provided by nature.”Tending to one’s inner life

Science and religion, therefore, were both integral to the soul of the Geniza person. There was no sense that these two pillars of thought challenged one another. By tending to their inner lives through rituals that helped them deal with the sadness and trepidation, and their bodies through the tools of medicine available to them, the Geniza people took a holistic approach to epidemics.

For them, following the medical advice of Maimonides or Ibn Rushd was an essential part of their response to plague. But while hunkered down in their homes, they also looked to the spiritual advice of these thinkers, and others, to care for their souls. Those of us experiencing stress, solitude and uncertainty amid the coronavirus pandemic could learn from the medieval world that our inner lives demand attention too.